Dr. Bill Saturno is in the news again for unearthing an ancient art studio in Guatemala. The post below is from July 2011, when I met him in Belize:

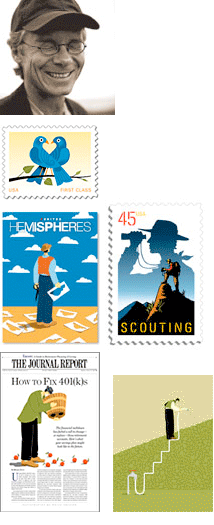

Dr. Bill Saturno has got to be America’s funniest archaeologist. His discoveries of Maya murals made page one of the New York Times. That’s him pictured above at an ancient Maya ballcourt in Caracol, Belize. He is built like John Belushi or Lou Costello, and like those great comics, he talks with more than his mouth. His eyes roll, his hands flutter, and he seems a surprised as anyone else to hear what he is saying.

I am on the road with a group of NEH fellows, most know much more about Maya art than I do. We heard Dr. Saturno tell his hair-raising story in a makeshift conference room in a funky Belizean hotel. We were supposed to meet Dr. Saturmo in the Peten, Guatemala, but a US State Dept. warning prompted by a recent massacre there led to a change of venue.

Currently at Boston University, Saturmo was an adjunct professor at University of New Hampshire in 2001. His life changed that March when he flew to Guatemala to do a brief project over Spring Break. He went into the Peten, the dense jungle territory near the borders of Mexico and Belize. His original Spring Break plan, Plan A, didn’t pan out, nor did Plan B.

A Guatemalan guide named Bernie Middlestadt suggested a Plan C. He told Saturno he might find upright monuments, Maya stela, at a looted site north of the famed ‘lost city’ of Tikal. Bernie was no ordinary guide. A steely-eyed Guatemalan of German descent, he was recommended by Saturno’s mentor, the British explorer Ian Graham. Graham’s autobiography is aptly titled, The Road to Ruins. According to Saturno, it is a ripping yarn, as the Brits say. Graham played parlor games at Rudyard Kipling’s house, served tea to the Grand Pasha at age 11, and cavorted with Picasso in Paris. All this, before dedicating himself to Maya studies.

Bernie led young Dr. Saturno and a crew of four on jungle journey that was supposed to be the proverbial ‘three hour tour.” The last road sign Saturno saw was an unhinged arrow pointing straight to hell. Felled trees forced the six to abandon their two vehicles. Saturno began to have doubts when Bernie’s men needed machetes to clear the path. He had a GPS, so he was never really lost. But it occured to him that knowing where you are is far less important than knowing where the hell you are going. They drank the last of their water. Bernie assured Saturno the Peten was full of shower vines. Cut the right way shower vines provide plenty of drinkable water, or so said Bernie.

Perhaps Saturno asked Bernie too many questions as they hacked their way forward. Bernie told a little jungle parable. Once upon a time, he was guiding a gringo, and the man stepped on a plant. Bernie informed his client that this plant was a very rare orchid. The man stepped on another orchid, and Bernie warned him politely not to do it again. When the gringo stepped on a third orchid, Bernie took out his pistol and shot him in the face. End of story. So, Saturno followed Bernie in silence and stepped exactly where Bernie stepped.

Zig-zagging north they encountered no shower vines, but Bernie promised to break out the emergency rations when they reached the site. The jungle is quick to cover ancient pyramids, so a Maya temple covered with trees and moss looks much like a hill. They found the site eventually, an overgrown hill with a looters’ tunnel. Saturno looked around. If there were stelea here, they were long gone.

Bernie and his men went looking for water vines. Saturno took refuge from the heat in the looters’ tunnel. It smelled of bat droppings. He pointed his flashlight up and found the first Maya murals in over half a century. He took a photo. He said he was so tired and dehydrated that he felt no elation. Just thirst. When Bernie and crew returned Saturno said nothing about the murals. It had occurred to him that perhaps Bernie was a looter.

Above is a painting by artist Heather Hurst, done over images scanned directly from the wall at San Bartolo.

Bernie broke out the emergency rations, a single serving of crab flavored Cup o’ Noodles for six men. They found a few ounces of muddy water. Bernie told Saturno they needed his shirt to strain the goopey liquid. Saturno thought, why my shirt? But then looking a the dirty, raggedy shirts of the others’ backs, he saw the wisdom in Bernie’s decision.

Retracing their steps through the jungle two of the men collapsed unconscious on the ground. Saturno said to himself – I don’t want to die on the jungle floor, so he strung his hammock between two trees and passed out. Sometime later Antonio, the eldest guide, returned with foraged bitter roots, and got Saturno and crew back to the vehicles. He made it home, and the rest is history.

Micheal Coe in his classic book The Maya, put it this way, “One of the great archaeological finds of all time took place in 2001, when Dr. William Saturno stumbled across San Bartolo…taking refuge from the intense sun in the shade of a looter’s tunnel.” Coe and I can’t tell it like Saturno. If you are at Boston University, sign up for his course.

Learn more, in Spanish or English at the San Bartolo project web site.

Note: Originally posted from my Ipad in Merida, Yucatan. Updated links a bit since.